Author: J.K. Ullrich, Bird TLC volunteer

The first six gifts in the carol “The Twelve Days of Christmas” are birds (seven, if you consider that “five golden rings” may have originally referred to goldfinches or the ringed plumage on a pheasant’s neck). To celebrate the holiday season, BirdTLC is reimagining the lyrics with native Alaskan birds. Visit our blog every week from now until the end of December for fun, festive facts about our wildlife.

What’s that feathery figure perched atop a spruce? Here in Alaska, it’s not a partridge in a pear tree, but more likely a Northern Hawk Owl. One of only a few owl species active during the day, this crow-sized raptor takes up a high post to scan for prey, relying more on sight than sound. When it detects a potential meal, it swoops in on stiff flight feathers that make its wingbeats as audible as any hawk’s.

The Northern Hawk Owl resembles its namesake in other ways. It shares treetop hunting habits with the Red-Tailed Hawk; its long tail and agile flight style are similar to the Cooper's Hawk; and its sharp ki-ki-ki-ki-ki-ki alarm call evokes an American Kestrel. Like other daytime predators, Hawk Owls have symmetrical ear openings. Although this makes their hearing slightly less sensitive than nocturnal owls with asymmetrical ear openings, they can still hear prey moving beneath a foot of snow.

Because of their hawk-like hunting style, Northern Hawk Owls prefer habitats with spaced trees, such as the taiga or boggy muskeg in Alaska’s interior. Prey availability influences their range. For example, a study in Denali National Park found that 94% of the resident Hawk Owls’ diets consisted of red-backed voles and mice; if the rodent population declined, the owls might move south in search of food. Ornithologists call this phenomenon irruption. (Other Alaskan species such as Common Redpolls and Red-Breasted nuthatches are also irruptive.)

Following the food helps Northern Hawk Owls—especially inexperienced young birds—survive lean seasons, but habitat loss puts them at risk. Audubon's climate model predicts that Northern Hawk Owls will lose all of their current summer range and 77% of their current winter range by 2080. The owls also face more immediate threats. Perching in exposed treetops makes them vulnerable to poachers, and flying low to the ground can cause collisions with vehicles.

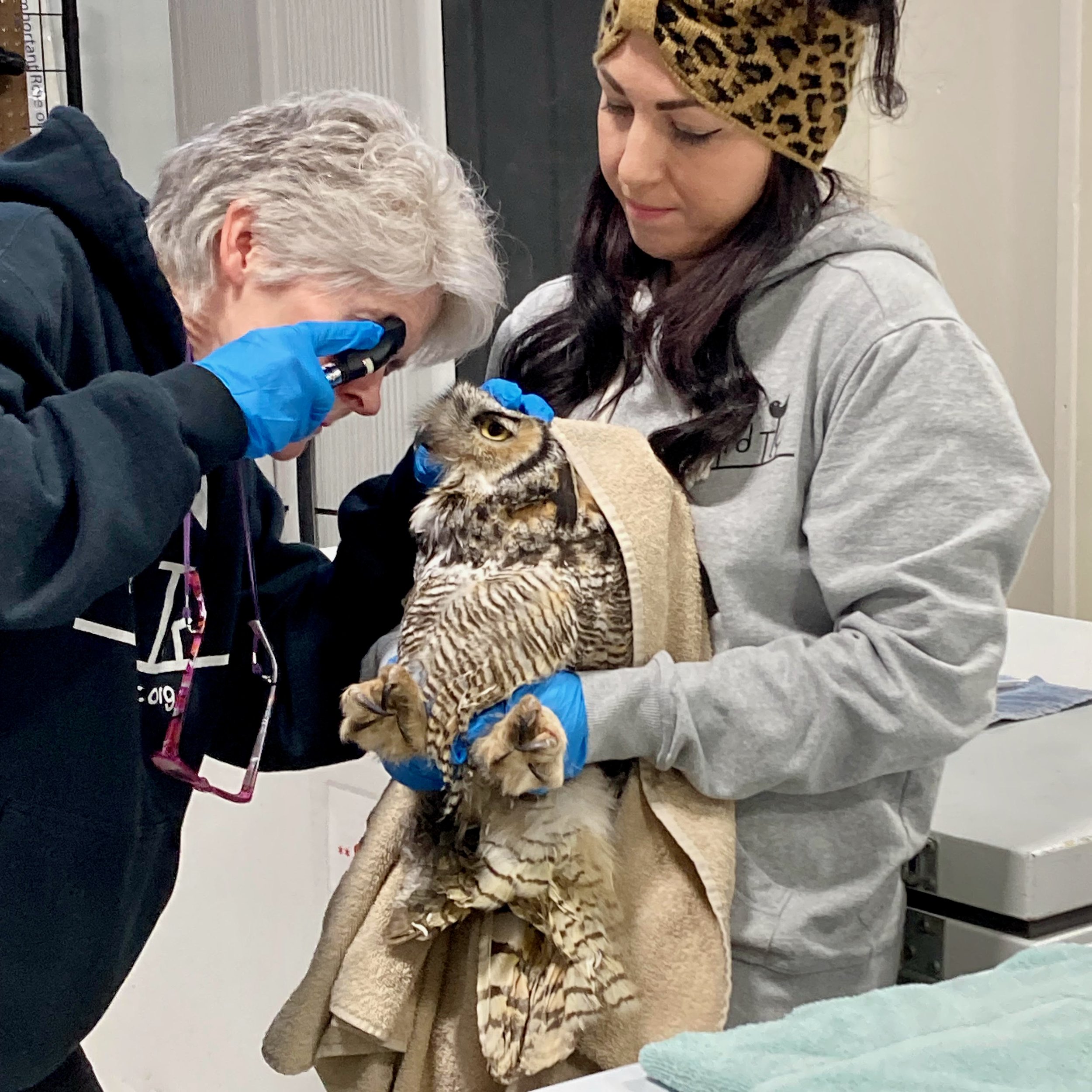

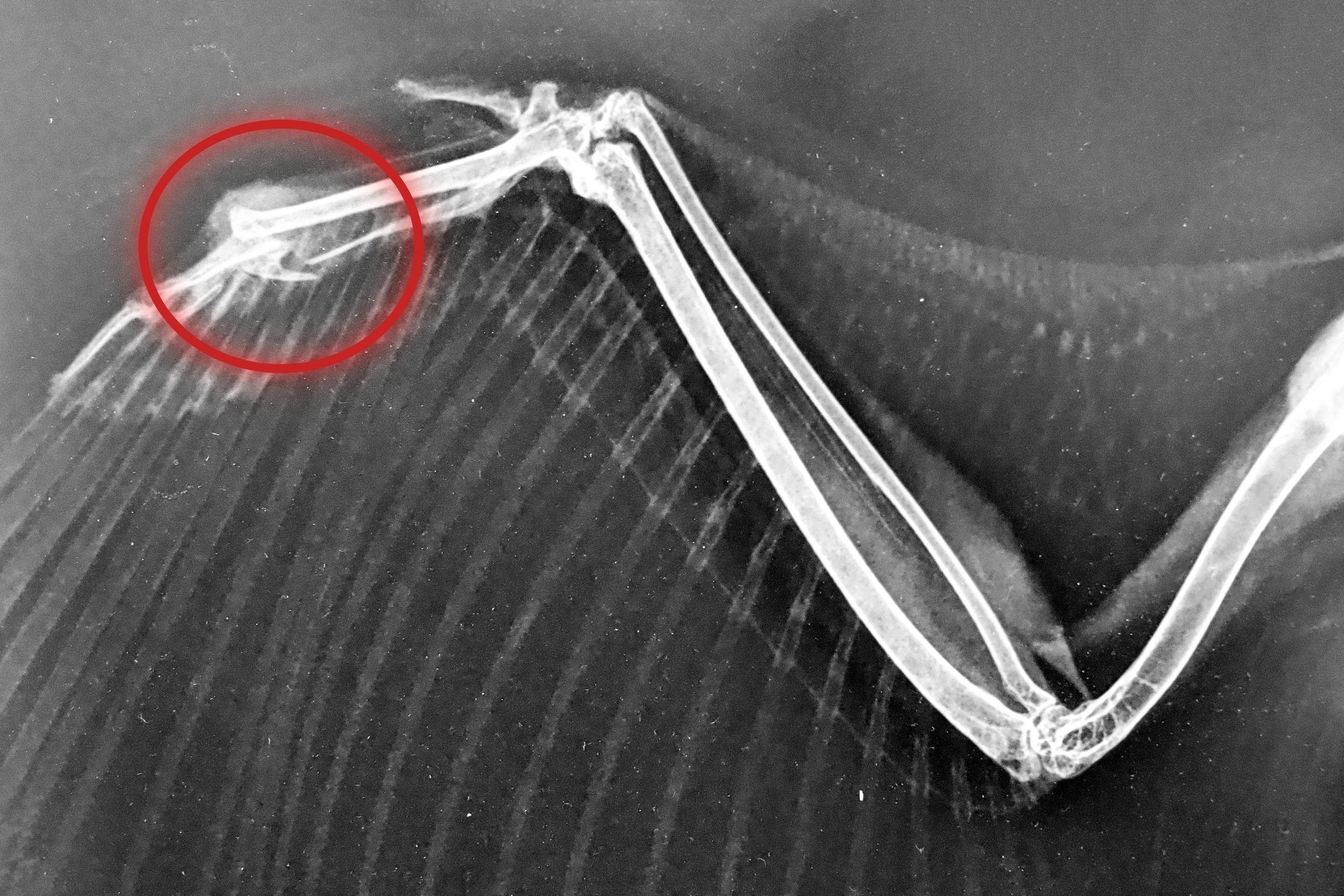

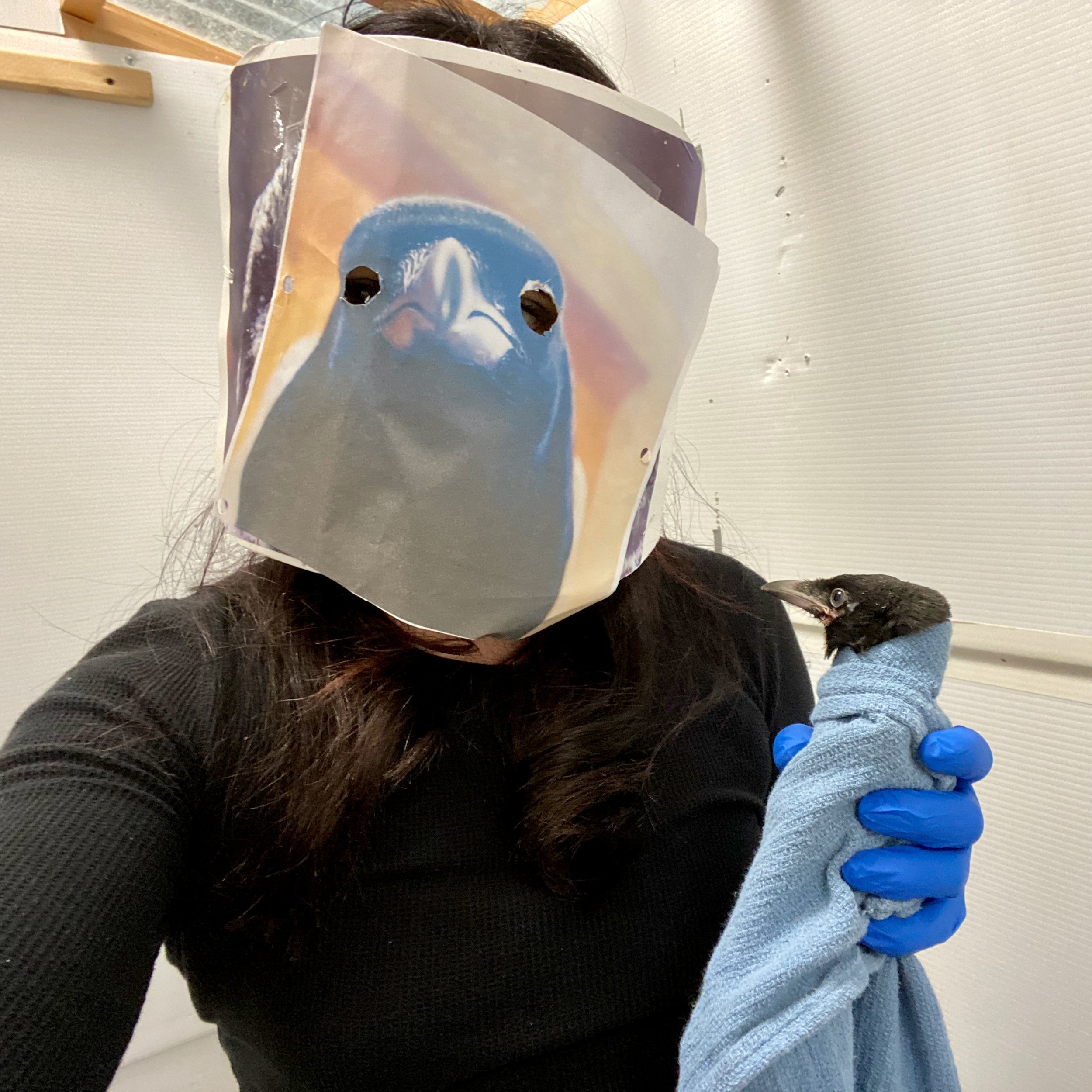

A car strike late last year brought a Northern Hawk Owl to BirdTLC with a broken wing bone. After a few weeks of care and rehabilitation, he returned to the wild in December 2023. This gift of a second chance came from our dedicated staff and supporters. We hope you’ll join us in the New Year as we advocate for Alaska’s birds, who bless us with beauty and biodiversity all year long.

Stay in touch with Bird Treatment and Learning Center!

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube