While summertime rescue birds are primarily orphaned chicks who need dedicated human foster parents, like those we introduced in August and September, a change of seasons brings different patients to Bird TLC. “In the winter, there are no healthy orphans. Every bird that comes in is a medical case,” says Avian Care Director Dr. Karen Higgs. Bird TLC’s 458th bird of the year was no exception, although it was rather exceptional: a Northern Hawk Owl, one of only two diurnal owl species in the world. They’re more common in Alaska’s interior, where open forests and bogs provide an ideal hunting environment, but this one was struck by a car along the coastal Seward Highway.

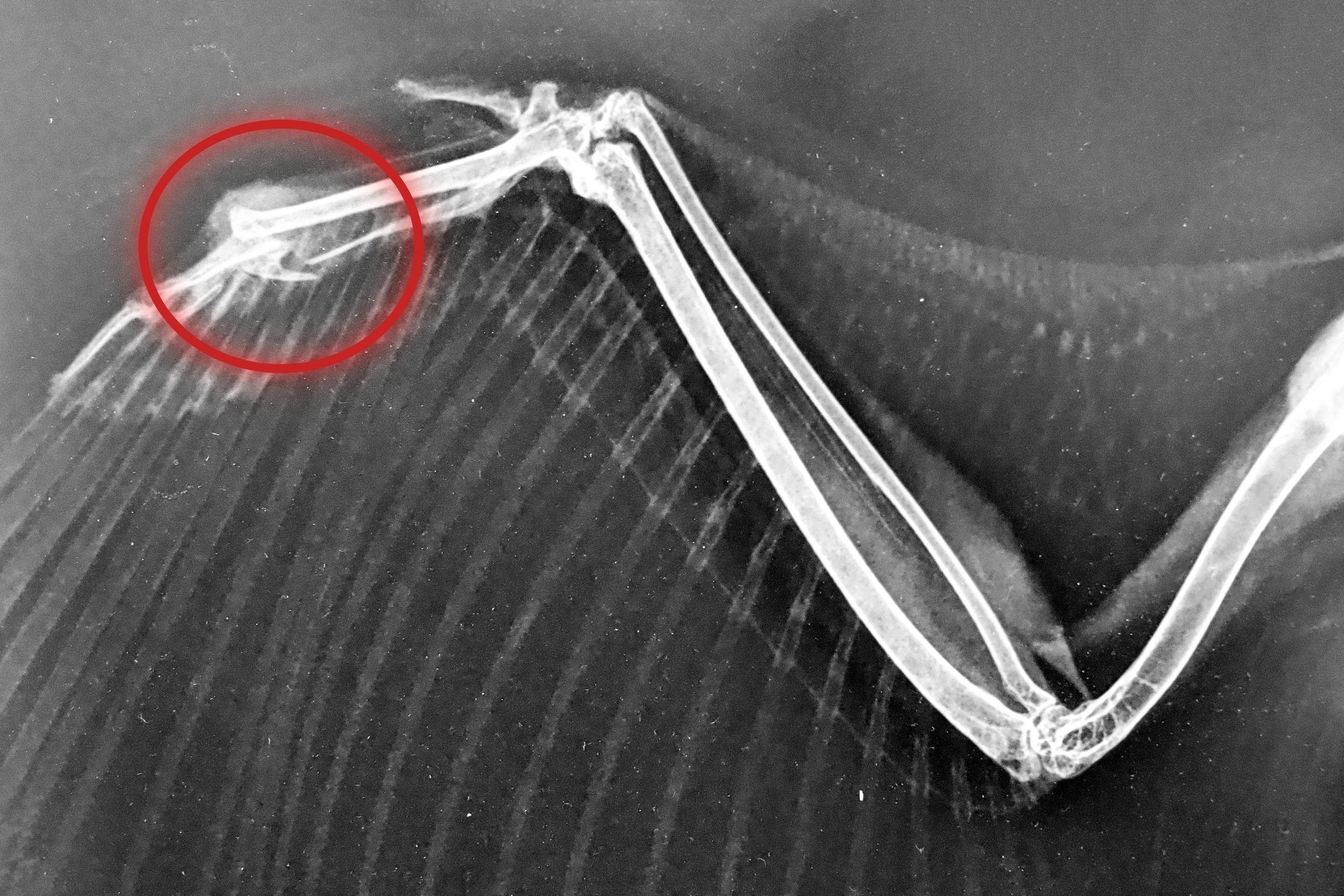

First taken to the Alaska Sealife Center in Seward, the owl transferred to Bird TLC for rehabilitation. X-rays revealed a fracture in the wrist-like bone of his right wing. Bird bones heal much more quickly than human bones—sometimes in only 7-10 days—so breaks can fuse crookedly without prompt intervention. This lucky owl arrived in time for treatment. Two weeks in a splint repaired the wing enough for physical therapy. Since birds can’t follow an exercise program, initial sessions take place under anesthesia, with a rehabilitator manipulating the limb. Once the injury stabilizes, the birds further strengthen their muscles through natural movement.

Flapping around an enclosure made the owl strong enough to fly again. Before discharge, Dr. Higgs performed a final checkup. She weighed the bird and assessed the wing’s range of motion. Except for a naughty finger nibble, the patient cooperated. This tolerant nature makes Northern Hawk Owls vulnerable to poaching. Vehicle collisions, entanglement with power lines, and predation from larger raptors also pose threats. Our owl had survived one such encounter, and the exam concluded that he had recovered well. He’d gained a few healthy grams (and tried to cache part of his rodent lunch for a later snack, normal behavior in the wild). Vibrant yellow eyes stared around the surgical room. After tidying a few damaged tail feathers, Dr. Higgs deemed the owl ready to return home.

But where was “home”? Rehabilitators try to release birds in the area where they were found; however, this owl was rescued along a highway, leaving his territory unclear. Tasha DiMarzio, a waterfowl biologist from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, analyzed local geography for a suitable spot. “Since this is a hawk owl, he likes the boreal forest habitat, which is black spruce mixed with some aspen and birch. Seward is a rainforest,” she explained. That meant balancing the region of origin with a habitat where the owl would thrive. DiMarzio scouted locations between Seward and Anchorage, evaluating conditions.

Winter weather complicated the decision. Ice crust atop the snow could inhibit the owl’s hunting technique: like their namesakes, Northern Hawk Owls spot prey from a high perch and pounce on it beneath the snow. Short daylight also left little time for the owl to find a roosting spot before nightfall. On the first day of December, DiMarzio and the owl raced the sunset back along the Seward Highway. With a beat of restored wings, the owl took off into its new landscape, carrying the hopes of Bird TLC’s dedicated crew. “There’s a lot of energy from the staff that goes into rehabilitation,” says DiMarzio, “so I try and think of the best habitat I can put this bird into, to give it its best chance.”

Bird TLC is grateful to all those involved with this bird’s rehabilitation - staff, volunteers, the Alaska Sealife Center, and Tasha DiMarzio.

Story and photos by Bird TLC volunteer J.K. Ullrich

You can help more birds be rehabilitated and released into the wild with your donation. Thank you.